HISTORY OF THE GREAT AMERICAN FORTUNES

CHAPTER V

THE BLAIR AND THE GARRETT FORTUNES

Of John I. Blair little is now heard, yet when he died in 1899, at the age of ninety-seven, he left a great personal fortune, estimated variously at from $60,000,000 to $90,000,000 ; his wealth, descending largely to his son, De Witt C. Blair, forms one of the notable estates in the United States. Here, according to the purveyors of public opinion, was an honest man ; here incontestably was a capitalist of rare business instinct, whose fortune came from pure, legitimate and upright methods. For more than half a century, said one newspaper editorial1 at his death, he has been one of the leading business men in the country, and for more than a quarter of a century one of the richest men in the world, his fortune being estimated at from $50,000,000 to $100,000,000, every farthing of which came to him through legitimate channels, creating other wealth on its way to him, as well as after it had reached his hands. This was not an isolated eulogy ; round and round the columns of the press went these pæans with never a dissent or demurring.

Of John I. Blair little is now heard, yet when he died in 1899, at the age of ninety-seven, he left a great personal fortune, estimated variously at from $60,000,000 to $90,000,000 ; his wealth, descending largely to his son, De Witt C. Blair, forms one of the notable estates in the United States. Here, according to the purveyors of public opinion, was an honest man ; here incontestably was a capitalist of rare business instinct, whose fortune came from pure, legitimate and upright methods. For more than half a century, said one newspaper editorial1 at his death, he has been one of the leading business men in the country, and for more than a quarter of a century one of the richest men in the world, his fortune being estimated at from $50,000,000 to $100,000,000, every farthing of which came to him through legitimate channels, creating other wealth on its way to him, as well as after it had reached his hands. This was not an isolated eulogy ; round and round the columns of the press went these pæans with never a dissent or demurring.

AN INQUIRY INTO BLAIRS CAREER.

Through all of these weary pages have we searched afar with infinitesimal scrutiny for a fortune acquired by honest means. Nor have the methods been measured by the test of a code of advanced ethics, but solely by the laws as they stood in the respective times. At no time has the discovery of an honest fortune rewarded our determined quest. Often we thought that we had come across a specimen, only to find distressing disappointment ; through all fortunes, large and small, runs the same heavy streak of fraud and theft, the little trader, with his misrepresentation and swindling, differing from the great frauds in degree only. Have we, at last, in Blairs, stumbled upon one fortune unblemished by any taint whatsoever ? Can we now exclaim, Eureka ! So it would seem if current comment is to be swallowed as the fact. But inasmuch as we have doggedly developed in exploring, if not a perversely skeptical turn of mind, let us gratify it to the full by investigating the career of this paragon of commercial virtue.

Now it does so happen that whatever the reserved, sequestered life Blair led in his dotage, basking in the titular glory of wonderful business man and philanthropist, he left a large, resounding impress upon industrial events of fifty and sixty years ago. The surviving records, buried in obscurity, emerge from their forgotten shelves to confound the fairy tales of present-day eulogists. He was contemporaneous with Commodore Vanderbilt, the first John Jacob Astor, and Russell Sage ; and he was as excellent a business man as any of them, which is to say, his methods were relatively the same as theirs. While Astor was proving his talent as a successful business man by debauching, swindling and murdering Indian tribes, and while Vanderbilt was blackmailing, and Sage was bribing and embezzling, Blair was demonstrating in his own way that he, too, had all the necessary qualifications of a leading business man.

Born near Belvidere, N.J., in 1802. his parents were farming folk ; and his biographers relate with a blissful smack of appreciation that when he was a very young boy he announced to his mother that, I could go in for education, but I intend to get rich. Like Sage, he started as a clerk in a country store, and he then widened into being the owner of a general merchandise store, at what is now Blairstown, New Jersey. Years passed and he prospered, his panegyrists tell, and he then opened a number of branch stores. But this part of his career is shrouded in mere tradition ; nothing authentic is known of his methods at the time.

BLAIR AS A RAILROAD BUILDER.

Blair next turned up as the owner of an iron foundry at Oxford Furnace, N.J., and it is from this point of his career that definite facts are embodied in official records. The necessity for transporting the metal to the seaboard, says one biographer, led Mr. Blair and others to organize the Lackawanna Coal and Iron Company, out of which has grown the great system of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. With this all-inclusive sentence the biographer airily dismisses this part of the subject. But there are weighty reasons why we should dwell upon it, with brief, yet sufficient explanation, for it was in this operation that Blair made his first millions ; it was here that he gave the first scintillating demonstrations of his rare business instincts.

Had it not been for an acrimonious falling out between him and his associates in this railroad business, the truth would be beyond reach. As it is, these men made the huge error of perpetuating their quarrel in print ; an unpardonable blunder if the good opinion of posterity is to be held. This quarrel arose over such a sordid matter as the allotment of graft ; it was a bitter, ungentlemanly row, as is all too clearly evidenced in the biting denunciations of one another that were put in the reports by the disputants themselves. From these reports it appears that Blair was, indeed, doing business in the accustomed style ; he was selling, at excessive prices, the products of his mill to a railroad corporation of which he was a director, and individually building branch lines which he foisted at enormous profit upon the corporation.

The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, now one of the very richest in the land, was organized in 1850 by the grouping of a number of small, separate lines. To secure franchises and special rights and aid, the usual procedure of bribery was resorted to, and with unfailing success. The men at the head of it knew their slippery trade well ; they were the same rich merchants who were involved in many another fraud. Some of them we have accosted before in these chapters George D. Phelps, John J. Phelps, William E. Dodge, Moses Taylor and others. With John I. Blair these men formed the board of directors of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company.

One of the separate lines incorporated in this railroad was the Warren line, crossing New Jersey into Pennsylvania. The building of this road, as nearly as can be made out from the law records, was attended with some very peculiar circumstances. Two sets of capitalists were competing for a franchise to extend their railroads through the mountains to the Delaware Water Gap ; one was the Morris and Essex Railroad Company, the other the Warren Railroad Company, headed by Blair and Dodge. Both, in 1851, obtained charters from the New Jersey Legislature within a few days of each others grant. In those years scandal after scandal was developed in successive New Jersey legislatures ; it was no secret that the railroad magnates not only debauched the Legislature and the common councils of the cities with bribes, but regularly, in true business-like style, corrupted the elections of the State. In 1851, for instance, the only candidates balloted for by the Legislature for the post of United States Senator were rival railroad nabobs ; the very same men who, it was notorious, had for years been bribing and corrupting.

Which of the two sets would succeed in building its railroad extension first ? The Legislature had accommodated both with charters for the same route ; in that respect they were on an equal footing. But Blair and Dodge completely outwitted the Morris and Essex set, and went on to claim prior rights for their lines. The Morris and Essex Railroad Company charged fraud and went hotfooted into court after an injunction, which temporarily it obtained. The case came up for final adjudication in the New Jersey Court of Chancery in 1854. The Morris and Essex group asserted that they had bought the right of way through the Van Ness Gap, and charged Blair with taking fraudulent possession of these lands for the purpose of fraudulently frustrating the complainants in the extension of their road ; that the survey made by Blair and Dodge was fraudulent, and that there were other frauds. In his answer Blair put in a general denial, although he admitted that the Morris and Essex Railroad Company had bought the land and received deeds for it, but averred that this took place after the lands had been conveyed to the Warren Railroad Company. Each side charged the other with fraud ; undoubtedly the assertions of both were correct. Judge Green decided in favor of Blair and dissolved the injunction.2 Subsequently the Warren railroad was unloaded upon the D., L. & W. at a great profit.

CHARGES OF JOBBERY AND GRAFTING.

At first, the relations among Blair, the Phelpses and Dodge must have been of that brotherly unity springing from the satisfactory apportioning of good things. Previous to 1856, the annual reports of the board of managers of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company breathed the most splendid harmony, with never a ripple of discord. As president of the company, Phelps had appointed Blair the land agent, for the Warren division of the railroad.3 Very evidently a joyous, comfortable spirit of satisfaction with the way things were progressing pervaded this stalwart group of worthies.

Suddenly the tenor of their private and public communications changed. Peppery statements, growing into broadsides, were issued, filled with charges and counter charges, and a caustic quarrel set in over the question of graft, especially in connection with the Warren railroad. On September 9, 1856, Phelps resigned from the presidency, and in doing so, practically charged others of the directors with carrying on a profuse system of grafting in the purchase of land ; supplies and branch lines.

Did Phelps resign as a protest ? More probably, the actual situation was that the internal fight sprang up over difficulty in adjusting the division of the spoils, and the anti-Phelps faction had proved itself the stronger. Phelps set forth his case in published confidential statements accompanying the annual reports. He boasted that after the franchises of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad had been forfeited for non-compliance, that it was he who had got through an act on April 2, 1885, restoring all franchises and granting other important privileges. He complained of the exorbitant expenditures the directors were making, and significantly pointed out that when he had wanted to get an auditor, Blair and other directors refused to vote for one. Referring to the process of graft Phelps wrote that one of our managers [Blair] is a director and large stockholder in the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company ; one-eighth owner in the Lehigh and Tobyanna Land Company ; largely interested in real estate along the line of the road and president of the Warren railroad, of which his son is a principal contractor. Another son is director and very large owner in the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company, etc.4 In another confidential circular, dated January 17, 1857, Phelps criticized Blair as one of the parties more particularly referred to and as systematically opposed to my measures. If this much came out in cold type, what must have been the whole story ? The fragmentary visions we get in these reports are undoubtedly but an index to the elaborate miscellanies of graft carried on by Blair in every available direction.5

BLAIRS RAILROADS IN THE WEST.

Blairs loot in these transactions appears to have been very large. His operations were so successful that he went into railroad founding as a regular pursuit ; and, as did Sage, he combined professional politics and business. His greatest opportunities came when the Union Pacific and other railroad charters, subsidies and land grants were bribed through Congress.

In the early days of the settlement of the great West, wrote one of his puffers, Mr. Blair found ample opportunity for the exercise of his rare judgment and untiring energy, and his name was connected, either as a builder or director, with not less than twenty-five different lines. What a symmetrical and appealing description ! All that it lacks to complete it are certain trivial details, which will here be supplied.

As one of the original directors of the Union Pacific Railroad, Blair shared in its continuous and stupendous frauds. But it was in Iowa that he plundered the most of his tens of millions Iowa with its fine pristine agricultural lands, among the richest in the United States. While Sage was busily engaged in thefts and expropriations in Wisconsin and Minnesota, he was also, as was Blair, pursuing precisely the same methods in Iowa. There was the same bribery of Congress and of Legislature ; the same story of immense subsidies and land grants corruptly secured ;6 the same outcome of thieving construction companies, looted railroads, the cheating of investors, bankruptcies and fraudulent receiverships. Not less than $50,000,000 in subsidies in one form or another were obtained by the railway companies in Iowa ; their land grants reached almost 5,000,000 acres. In the projection of the railroads in that State, Blair was the predominating almost, excepting Sage, the exclusive figure ; he seemed to direct everything ; and he certainly allowed no one else to pocket what he could get away with himself.

As one of the original directors of the Union Pacific Railroad, Blair shared in its continuous and stupendous frauds. But it was in Iowa that he plundered the most of his tens of millions Iowa with its fine pristine agricultural lands, among the richest in the United States. While Sage was busily engaged in thefts and expropriations in Wisconsin and Minnesota, he was also, as was Blair, pursuing precisely the same methods in Iowa. There was the same bribery of Congress and of Legislature ; the same story of immense subsidies and land grants corruptly secured ;6 the same outcome of thieving construction companies, looted railroads, the cheating of investors, bankruptcies and fraudulent receiverships. Not less than $50,000,000 in subsidies in one form or another were obtained by the railway companies in Iowa ; their land grants reached almost 5,000,000 acres. In the projection of the railroads in that State, Blair was the predominating almost, excepting Sage, the exclusive figure ; he seemed to direct everything ; and he certainly allowed no one else to pocket what he could get away with himself.

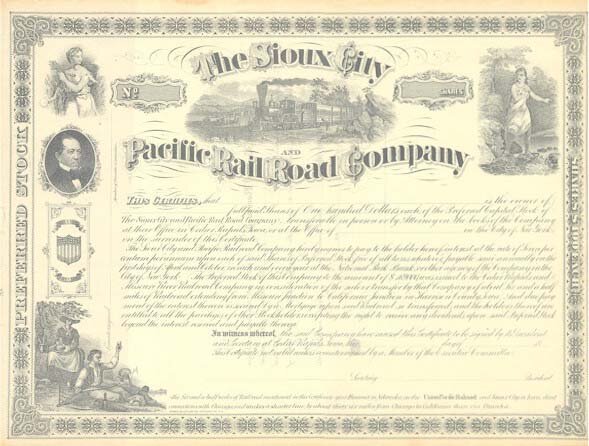

THE SIOUX CITY AND PACIFIC FRAUDS.

One of a number of his railroads was the Sioux City and Pacific a line with a very ambitious name but of modest length. Its charter, subsidies and land grant were obtained by Blair at the auspicious and precise time when the Union Pacific measures were passed by bribery.

One of a number of his railroads was the Sioux City and Pacific a line with a very ambitious name but of modest length. Its charter, subsidies and land grant were obtained by Blair at the auspicious and precise time when the Union Pacific measures were passed by bribery.

Whether, however, Blair used money in corrupting Congress is not to be determined from the official records. But if he did not, he, at any rate, employed an even more subtle and effective mode of corruption. The Congressional investigations reveal that it was his system to debauch members of Congress with gifts of stock in his corporations ;7 these honorable members, of course, mightily protested that they had paid for it, but nobody believed their excuses. Poors Railroad Manual for 1872-73 additionally reveals that among the directors and stockholders of Blairs railroads were some of the identical members of Congress, both of the House and Senate, who had advocated and voted for the charters, subsidies and land grants for these railroads.

For the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Blair secured a land grant of one hundred sections, and $16,000 of Government bonds, for each mile of railroad. What happened next ? Act two was the organization of a construction company modeled on exactly the same lines as the Credit Mobilier. As the head of this company, Blair extorted large sums for building the railroad. On the prairies of Iowa, with almost no grading necessary, railroad building called for comparatively little expenditure. Expert testimony before the Pacific Railroad Commission, in 1887, estimated that the road could have been built at a cost of $2,600,000, with the supplementary statement (and what a commentary it formed upon the business standards of the times !) that if honestly done the entire cost ought not to have exceeded $1,000,000.

For the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Blair secured a land grant of one hundred sections, and $16,000 of Government bonds, for each mile of railroad. What happened next ? Act two was the organization of a construction company modeled on exactly the same lines as the Credit Mobilier. As the head of this company, Blair extorted large sums for building the railroad. On the prairies of Iowa, with almost no grading necessary, railroad building called for comparatively little expenditure. Expert testimony before the Pacific Railroad Commission, in 1887, estimated that the road could have been built at a cost of $2,600,000, with the supplementary statement (and what a commentary it formed upon the business standards of the times !) that if honestly done the entire cost ought not to have exceeded $1,000,000.

A LITTLE ITEM OF A $4,000,000 THEFT.

What did Blairs company (which was mainly himself and his sons) charge ? It awarded itself $49,865 a mile, or a total of more than $5,000,000. Then having bled the railroad into insolvency, Blair enriched himself further by selling it to the Chicago and Northwestern Rail road Company. If there be any doubt of the cool deliberation with which those eminent capitalists set out to swindle the Government, it must, perforce, be dissipated by consideration of the following fact : When the negotiations were pending for the transfer of the stock of the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Company to the Chicago and Northwestern, reads the report of the Pacific Railroad Commission, John I. Blair offered a resolution, which appears on the minutes, setting forth that the Chicago and Northwestern must bind itself to protect every obligation of the company except that to the United States Government.8 This was a refreshingly candid way of arranging swindles in advance. And, in fact, the final swindling of the Government of much of the funds that it had advanced was accomplished in 1900. By an act then lobbied through Congress, the company was virtually released from paying back more than one-tenth of the sum it still owed the Government.10

What did Blairs company (which was mainly himself and his sons) charge ? It awarded itself $49,865 a mile, or a total of more than $5,000,000. Then having bled the railroad into insolvency, Blair enriched himself further by selling it to the Chicago and Northwestern Rail road Company. If there be any doubt of the cool deliberation with which those eminent capitalists set out to swindle the Government, it must, perforce, be dissipated by consideration of the following fact : When the negotiations were pending for the transfer of the stock of the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Company to the Chicago and Northwestern, reads the report of the Pacific Railroad Commission, John I. Blair offered a resolution, which appears on the minutes, setting forth that the Chicago and Northwestern must bind itself to protect every obligation of the company except that to the United States Government.8 This was a refreshingly candid way of arranging swindles in advance. And, in fact, the final swindling of the Government of much of the funds that it had advanced was accomplished in 1900. By an act then lobbied through Congress, the company was virtually released from paying back more than one-tenth of the sum it still owed the Government.10

ANOTHER RAILROAD PLUNDERED.

But Blairs frauds in the inception and construction of the Sioux City and Pacific and some of his other roads were surpassed in degree, at least by those he put through in another of his Iowa railroad projects the Dubuque and Sioux City line. The charter and land grants of this railroad, and those of the Iowa Falls and Sioux City Railroad, were given by an act passed by Congress on May 15, 1856. We have seen what indiscriminate corruption was going on in Congress in 1856 and accompanying years ; how the Des Moines River and Navigation Companys land grant was obtained by bribery, and how committees were reporting the existence of corrupt combinations in Congress. There is no definite official evidence that the charter and land grants of the Dubuque and Sioux City Railroad Company and those of the Iowa Falls and Sioux City were secured by bribery, but judging by the collateral circumstances attending the passage of other bills at the same time, the probabilities are strong that they were. By the act of 1856 these two companies received as a gift about 1,200,000 acres of public land in Iowa. Despite this lavish present, the incorporators made little or no attempt to build the entire railroad ; they occupied themselves almost solely with stockjobbing, and with the business of profitably disposing of the land to settlers. Congress was compelled under pressure of public opinion to forfeit much of their land grant.

CORRUPTING OF CONGRESS.

Blair saw what glorious opportunities had been lost by the act of forfeiture. But the mischief could be undone. If one set of capitalists were obtuse enough not to know how a restoration could be brought about, he knew. So he came forward, took up the companies as his own, and applied to Congress and to the Legislature of Iowa for a resumption of the rights and grants of which they had been shorn.

He succeeded ; both Congress and the Iowa Legislature passed acts in 1868 restoring the rights and land grant. How came it that he encountered no obstacles in his plan ? Why were these legislative bodies so tractable ? Of course, they could plead that they simply acted in deference to memorials from the citizens of Iowa ; but memorials were transparent affairs, easily manufactured. And the Wilson Committee (the Credit Mobilier Investigation) of 1872 could make its whitewashing report that no evidence could be found of money having been used for improper purposes, either in Congress or in the Iowa Legislature. But the testimony before this very committee flatly contradicted its conclusions. It was revealed that a whole string of conspicuous members of Congress had suddenly become large stockholders in the Dubuque and Sioux City Railroad.10a Upon getting the restoration of the land grant, Blair organized a construction company, called the Sioux City Railroad Contracting Company, and by the usual cumulative system of frauds in construction work, made immense profits, reaching many millions of dollars. Some of the railroads that Blair plundered are now parts of the Illinois Central system, of which Harriman became dictator.

It must not be thought, however, that outright bribery was always resorted to in order to secure subsidies, special rights and immunities. In the first stages of railroad history direct bribery was the usual means ; but as time wore on, the passing of money in direct forms became less frequent, and a less crude, finer and more insidious system of bribery was generally substituted. The Western magnates began to follow the advice of that Eastern magnate who declared that it was easier to elect, than to buy, a legislature.

BRIBERY BY MONEY AND OTHERWISE.

The newer system as it was carried on in Iowa and other states was succinctly described in 1895 by William Larrabee, erstwhile Governor of Iowa. Outright bribery, he wrote, with a long and keen knowledge of the facts,

is probably the means least often employed by corporations to carry their measures. . . . It is the policy of the political corruption committees of corporations to ascertain the weakness and wants of every man whose services they are likely to need, and to attack him, if his surrender should be essential to their victory, at his weakest point. Men with political ambition are encouraged to aspire to preferment, and are assured of corporate support to bring it about. Briefless lawyers are promised corporate business or salaried attorneyships. Those in financial straits are accommodated with loans. Vain men are flattered and given newspaper notoriety. Others are given passes for their families and their friends. Shippers are given advantages in rates over their competitors. The idea is that every legislator shall receive for his vote and influence some compensation which combines the maximum of desirability to him with the minimum of violence to his self-respect. ... The lobby which represents the railroad companies at legislative sessions is usually the largest, the most sagacious and the most unscrupulous of all. In extreme cases influential constituents of doubtful members are sent for at the last moment to labor with their representatives, and to assure them that the sentiment of their districts is in favor of the measure advocated by the railroads. Telegrams pour in upon the unsuspecting members. Petitions in favor of the proposed measure are also hastily circulated among the more unsophisticated constituents of members sensitive to public opinion, and are then presented to them as an unmistakable indication of the popular will. . . . Another powerful reinforcement of the railroad lobby is not infrequently a subsidized press and its correspondents.

But the robbery by means of construction companies in his numerous railroad projects formed only a part of the wealth grasped by Blair. One-eighth of the entire domain of the richly fertile State of Iowa was granted to railroads, most of which Blair owned. This reached an area almost as large as the State of Massachusetts. Settlers were compelled to pay an exorbitant price for farm lands, and very often were under mortgage to the railroad companies. A detailed description of Blairs methods would be simply a repetition of those described in previous chapters in the case of other magnates.

PHILANTHROPY COMPARED WITH FACT.

Although incurably stingy in personal expenditures the meanest of men Blair donated just enough money to procure the award of being an extremely pious philanthropist. He founded one hundred churches in the West ; he established a Presbyterian Academy at a cost of $150,000, and gave several hundred thousand more dollars to the Presbyterian Church. But what were the effects of his frauds and oppressions and those of his successors upon the very people to whom he so devoutly contributed pulpits and gospels ? Writing of the Iowa railroads, Dr. Frank H. Dixon, a conservative writer, says :

The roads had it in their power to make and unmake cities, to destroy the businesses of individuals, or to force their removal to favored points. The people were quickly up in arms against this policy. The flame of opposition was fanned by the bitter feelings aroused through absentee ownership, so prevalent in the Western States at this time. A well-settled conviction possessed the people that the owners of capital, directing their operations in absentia and through intermediaries, limited their interest in Western affairs to the amount of dividends which they could squeeze from the shippers.11

And, of course, the large amounts of watered stock, upon which these dividends had to be paid, were issued to cover the gigantic frauds of the railroad constructors and of succeeding groups of manipulators.

This, in outline, was the course of Blair, so eminent and exalted a capitalist ; here is an elucidation of the fine textures of his rare business instincts; and knowing it, the mystery of where his sixty or ninety millions came from is quite apparent, if not entirely clear.

What Blair and others were doing in the North and West before, during, and after the Civil War, John W. Garrett and Johns Hopkins were doing in Maryland. Scarcely referred to now, Garrett was extolled in his day as a famous railroad king; and in this case it is not the man so much nor the Garrett fortune which commands interest as is the story of the railway line that he and Hopkins largely owned ; this property forms to-day one of the great transportation systems of the country.

THE BALTIMORE AND OHIO BUILT BY PUBLIC MONEY.

As were other railroads, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was built almost wholly with funds granted by State, counties and municipalities. In 1827 the State of Maryland granted a subscription of $500,000 as first aid, and the city of Baltimore the same sum. At the outset the projectors loftily disclaimed any intention of asking any further grants of public aid ; private capital, said they, would construct the road. But seven years later they made another inroad upon the public treasury ; the State of Maryland was induced to subscribe $3,000,000 more in 1835, and the city of Baltimore $3,000,000 in 1836. In 1838 they obtained $1,000,000 from the city of Wheeling.12 For a while they were discreet enough to refrain from again attacking the public treasury ; but when, in 1850, they applied to the Common Council of Baltimore for $5,000,000 more, and obtained the amount, there was some questioning as to what had become of the many millions contributed from the public exchequer. A considerable part, it was evident, had been used in constructing the railroad, but opinions were freely expressed that the directors had been enriching themselves by the customary grafting devices of the day such as, for instance, those used by Blair in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York.

Whenever, however, opposition to additional appropriations sprang up and embarrassing questions were asked, the directors would have their glittering arguments ready. See what a great work we have been carrying on. Is this not an enterprise of the greatest importance to the whole community, to the farmer, the mechanic and the business man ? Now, when we are on the high road to completion, shall we have to suspend because of lack of funds ? Would not this be a great public calamity ? Such arguments told with the public ; and the legislatures and common councils, corruptly influenced, could always base their explanations upon them.

GARRETT AND HOPKINS GET CONTROL.

Plundered by the original clique, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad went into financial ruin. Notwithstanding the great bounties that it had received, it was in a demoralized condition in 1856, and its treasury was empty. Garrett and Hopkins, who had long been associated with it and who had probably shared in the loot (although there is no specific proof on this point), bought up more quantities of its stock, then selling cheap, and snatched control. Born in Baltimore in 1820, Garrett was the son of a rich shipping merchant ; Hopkins had made money in the grocery business.

Garrett and Hopkins not only continued the long prevailing frauds, but put through many other fraudulent and corrupt acts. Here, for example, is one of the smaller frauds : The millions of stock subscriptions donated by the State of Maryland for the building of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had been to a large extent floated in London among British capitalists. The interest had to be paid by Maryland to these financiers in gold. Did the company, on its part, reimburse the State in coin ? By no means. It claimed, by force of certain judicial decisions, that it was not required to pay interest to the State otherwise than in currency. Under the prevailing money conditions, and estimating the difference in rates of exchange, this form of payment meant a constant loss to the State of Maryland a loss reaching more than a total of $400,000, of which amount the Baltimore and Ohio cheated the State.

Far greater were the amounts of which the State of Maryland was cheated in the fraudulent manipulation of what was called the Washington Branch of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In return for franchises and aid, the company agreed to pay the State one-fifth of the passenger receipts. After the branch was in successful operation, its treasury was constantly represented as so sickly that there was no money in hand with which to pay the State. Time after time inquiries were made by honest legislators as to where the great profits had gone. No satisfactory answer was ever given ; the State was absolutely cheated ; and, finally, a corrupt act was passed practically abandoning all of the States claims.

Under Garrett and Hopkins control, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company caused a series of measures to be passed exceeding in corruption, in some respects, those put through by Commodore Vanderbilt in New York. Repeatedly the legislatures of Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and other States, and the common councils of many cities, were bought up, and the courts were thoroughly subverted. Franchises of inestimable value were given away ; the public treasury was cheated out of the sums advanced, and was drawn upon to pay the expense of improvements ; large stock watering issues were authorized, and the company was virtually relieved from taxation. By 1876 fully $88,000,000 of its property went untaxed.

The militant object of Garrett and Hopkins was the destruction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal as a competitor. As Commodore Vanderbilt in New York found the Erie Canal to be a competitor of his lines, so Garrett and Hopkins decided that they could not get a monopoly of transportation in Maryland until the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal had been extinguished as a competitor. The obstacles in their way were great, for the State of Maryland had expended many millions of public money in the construction of the canal, and owned it, and the public was not disposed to see its usefulness impaired. This was especially true of the merchant class, which demanded competition and insisted that monopoly would be ruinous.

DESTROYING CANAL COMPETITION.

Beginning in 1860, Garrett and Hopkins corrupted the Maryland Legislature, until by one act piled upon another, they were gradually able to wrest away its ownership from the State. But they did not merely depend upon the bribing of legislators after they were in office. With money supplied by Garrett and Hopkins, the political bosses of Maryland engaged in packing of primaries, indiscriminate bribery of voters and stuffing of ballot boxes, thus insuring the election of subservient officials. Once the canal was practically in their hands, Garrett and Hopkins made it useless as a competitor.

Having a complete monopoly they now exacted extortionate charges for transportation, and they likewise increased their profits by cutting the pay of their employes. In desperation, the railroad workers declared a strike in 1877. False reports of the violence of the strikers were immediately dispatched broadcast. Using these charges as a pretext, the military was called out. At Martinsburg, W. Va., the State militia refused to fire upon the strikers, but a company of militia, recruited from a class hostile to the strikers, opened fire, killing many of the strikers and wounding others.

HOPKINS BECOMES A PHILANTHROPIST.

Both Garrett and Hopkins extorted out large sums from their control and manipulations of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Hopkins fortune, at his death, amounted to nominally $10,000,000. At the time of his demise, in 1873, he was the wealthiest citizen of Baltimore. The most closefisted of men, he relaxed in at least one respect during the last year of his life. Following the example of so many other multimillionaires of the period, he made certain of the perpetuation of his memory as a great philanthropist. To this end, in March, 1873, he gave property valued at $4,500,000 with which to found a hospital in Baltimore ; he presented Baltimore with a public park, and he donated $3,500,000 as an initial benefaction for the founding of the Johns Hopkins University. Here it is pertinent to inquire what was the form of property given in these bounties. Very largely, it consisted of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad stock ; it was property representing the corruption of public life, the abasement of the workers and the general spoliation of the entire community.

And what was Garretts share of the proceeds of the joint control ? At his death, in 1884, it was said to be $15,000,000, but it was undoubtedly much more. This wealth descended to his son Robert, who went through a series of personal excesses, to wind up in melancholia and softening of the brain. Obviously enough, he was no match for those abler capitalists, the Vanderbilts, Goulds and Scott ;13 they pounced upon him and ruthlessly despoiled him as his father had despoiled others ; his autocratic power and sway gradually vanished. When he died, in 1896, his wealth had shrunk to about $5,000,000, and the Baltimore and Ohio system had passed under the control of the Pennsylvania railroad group of magnates.

1 New York Tribune, August 27, 1899.

2 New Jersey Equity Reports, ix: 635-649.

The chief owner of the Morris and Essex Railroad was Edward A. Stevens who, for many years, blackmailed a competing line, the New Jersey Transportation Company, and, who, when that company finally refused to continue to pay blackmail, bribed, it was charged, the New Jersey Legislature to pass retaliatory measures. See Chapter vii of present volume.

3 Second Annual Report of the Board of Managers of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company, 1855:8.

4 Confidential Statement to the Stockholders of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company, 1856:6.

5 Grossly pliable as the law has been, where capitalist interests have been concerned, nevertheless the law has long professed to recognize the fundamental principle that it was against public policy to let contracts for the construction of a railroad to a director or officer of the company. All such contracts, says Elliott, are regarded with keen suspicion, and, at least in the absence of good faith, are voidable, or, according to some authorities, void, upon the clearest principles of public policy. (See Elliott on Railroads, ii: 839-840.) This sounds well in theory, but in practice the courts have invariably found grounds to sanction these frauds.

6 The first land grants made by Congress, wrote Governor J.G. Newbold of Iowa, in his annual message in 1878, were turned over to the companies absolutely, although the act of Congress contemplated the sale of the lands by the State as earned, and the devotion of the proceeds to the construction of the railroads ; the companies were permitted to select the lands regardless of their line of road ; and they were allowed, virtually, their own time to complete the work, notwithstanding that one main object of the grants was to secure this completion at an early day.

Townships, towns and cities have been permitted to tax property within their limits to help build the roads, and the revenue thus derived was turned over absolutely to the companies constructing them, while much of the property of these companies practically escapes municipal taxation. Iowa Documents, 1878, Reports of State Officers: 27.

7 See Credit Mobilier Reports. These are full of testimony attesting the buying up of members of Congress by this method.

His chief accomplices in this work in Congress were William B. Allison and Oakes Ames. As Representative, and later United States Senator, from Iowa, Allison was long a powerful Republican politician. Ames (as we have seen) was one of the principal originators and manipulators of the great Credit Mobilier swindle (see Chapter xii, Vol. ii). The fact that Allison and Ames were both officers of the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Company at the same time that they were members of Congress was well known before the act of 1868 was passed. On December 15, 1867, Blair certified to Hugh McCulloch, United States Secretary of the Treasury, that the following officers of the company had been elected on August 7, 1867 : John T. Blair, president ; William B. Allison, vice-president ; John M.S. Williams of Boston, treasurer, etc. The Executive Committee elected on that date was composed of Blair, Ames, Charles A. Lambard, D.C. Blair, and William B. Allison. See Ex. Documents, Nos. 181 to 252, Second Session, Fortieth Congress, 1867-68, Doc. No. 203.

8 Pacific Railroad Commission, i:193.

9 Allison, who, as a prominent member of the House, had been implicated in Blairs briberies nearly forty years before, was now one of the leaders in the United States Senate. This was the man at whose death the newspapers eulogized as a great constructive statesman.

10 The act of May 15, 1856, gave a total of 1,233,481.70 acres to the Dubuque and Sioux City Railroad Company and the Iowa Falls and Sioux City Railroad Company. By the same act the Iowa Central Air Line and the Cedar Rapids and Missouri River Railroad Company received a total of 783,096.53 acres, supplemented by 347,317.64 acres by act of June 2, 1864. The acts of May 15, 1856, and June 2, 1864, also gave extensive land grants to the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad Company.

10a See the section of the Credit Mobilier Reports entitled Credit Mobilier and Dubuque and Sioux City, in which the details are set forth.

11 State Railroad Control, With a History of Its Development in Iowa:24.

12 Laws, Ordinances and Documents Relating to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company ; 1840:67, 108, 133, 134, etc.

13 A current story, frequently published, was to this effect : That Robert Garrett had secretly consummated negotiations for the purchase of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, and the night before the final arrangements were to be made invited a friend to celebrate the occasion. When bibulous from champagne, Garrett revealed the secret. The friend excused himself, went immediately to Scott, of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and informed that magnate. Scott at once filled a satchel full of bonds, and hurried away to make an offer to the capitalists controlling the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, outbid Garrett, and had secured the ownership of that railroad for the Pennsylvania system almost before Garrett had awakened from his drunken stupor.

Of John I. Blair little is now heard, yet when he died in 1899, at the age of ninety-seven, he left a great personal fortune, estimated variously at from $60,000,000 to $90,000,000 ; his wealth, descending largely to his son, De Witt C. Blair, forms one of the notable estates in the United States. Here, according to the purveyors of public opinion, was an honest man ; here incontestably was a capitalist of rare business instinct, whose fortune came from pure, legitimate and upright methods. For more than half a century, said one newspaper editorial1 at his death, he has been one of the leading business men in the country, and for more than a quarter of a century one of the richest men in the world, his fortune being estimated at from $50,000,000 to $100,000,000, every farthing of which came to him through legitimate channels, creating other wealth on its way to him, as well as after it had reached his hands. This was not an isolated eulogy ; round and round the columns of the press went these pæans with never a dissent or demurring.

Of John I. Blair little is now heard, yet when he died in 1899, at the age of ninety-seven, he left a great personal fortune, estimated variously at from $60,000,000 to $90,000,000 ; his wealth, descending largely to his son, De Witt C. Blair, forms one of the notable estates in the United States. Here, according to the purveyors of public opinion, was an honest man ; here incontestably was a capitalist of rare business instinct, whose fortune came from pure, legitimate and upright methods. For more than half a century, said one newspaper editorial1 at his death, he has been one of the leading business men in the country, and for more than a quarter of a century one of the richest men in the world, his fortune being estimated at from $50,000,000 to $100,000,000, every farthing of which came to him through legitimate channels, creating other wealth on its way to him, as well as after it had reached his hands. This was not an isolated eulogy ; round and round the columns of the press went these pæans with never a dissent or demurring. As one of the original directors of the Union Pacific Railroad, Blair shared in its continuous and stupendous frauds. But it was in Iowa that he plundered the most of his tens of millions Iowa with its fine pristine agricultural lands, among the richest in the United States. While Sage was busily engaged in thefts and expropriations in Wisconsin and Minnesota, he was also, as was Blair, pursuing precisely the same methods in Iowa. There was the same bribery of Congress and of Legislature ; the same story of immense subsidies and land grants corruptly secured ;

As one of the original directors of the Union Pacific Railroad, Blair shared in its continuous and stupendous frauds. But it was in Iowa that he plundered the most of his tens of millions Iowa with its fine pristine agricultural lands, among the richest in the United States. While Sage was busily engaged in thefts and expropriations in Wisconsin and Minnesota, he was also, as was Blair, pursuing precisely the same methods in Iowa. There was the same bribery of Congress and of Legislature ; the same story of immense subsidies and land grants corruptly secured ; One of a number of his railroads was the Sioux City and Pacific a line with a very ambitious name but of modest length. Its charter, subsidies and land grant were obtained by Blair at the auspicious and precise time when the Union Pacific measures were passed by bribery.

One of a number of his railroads was the Sioux City and Pacific a line with a very ambitious name but of modest length. Its charter, subsidies and land grant were obtained by Blair at the auspicious and precise time when the Union Pacific measures were passed by bribery. For the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Blair secured a land grant of one hundred sections, and $16,000 of Government bonds, for each mile of railroad. What happened next ? Act two was the organization of a construction company modeled on exactly the same lines as the Credit Mobilier. As the head of this company, Blair extorted large sums for building the railroad. On the prairies of Iowa, with almost no grading necessary, railroad building called for comparatively little expenditure. Expert testimony before the Pacific Railroad Commission, in 1887, estimated that the road could have been built at a cost of $2,600,000, with the supplementary statement (and what a commentary it formed upon the business standards of the times !) that if honestly done the entire cost ought not to have exceeded $1,000,000.

For the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Blair secured a land grant of one hundred sections, and $16,000 of Government bonds, for each mile of railroad. What happened next ? Act two was the organization of a construction company modeled on exactly the same lines as the Credit Mobilier. As the head of this company, Blair extorted large sums for building the railroad. On the prairies of Iowa, with almost no grading necessary, railroad building called for comparatively little expenditure. Expert testimony before the Pacific Railroad Commission, in 1887, estimated that the road could have been built at a cost of $2,600,000, with the supplementary statement (and what a commentary it formed upon the business standards of the times !) that if honestly done the entire cost ought not to have exceeded $1,000,000. What did Blairs company (which was mainly himself and his sons) charge ? It awarded itself $49,865 a mile, or a total of more than $5,000,000. Then having bled the railroad into insolvency, Blair enriched himself further by selling it to the Chicago and Northwestern Rail road Company. If there be any doubt of the cool deliberation with which those eminent capitalists set out to swindle the Government, it must, perforce, be dissipated by consideration of the following fact : When the negotiations were pending for the transfer of the stock of the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Company to the Chicago and Northwestern, reads the report of the Pacific Railroad Commission, John I. Blair offered a resolution, which appears on the minutes, setting forth that the Chicago and Northwestern must bind itself to protect every obligation of the company except that to the United States Government.

What did Blairs company (which was mainly himself and his sons) charge ? It awarded itself $49,865 a mile, or a total of more than $5,000,000. Then having bled the railroad into insolvency, Blair enriched himself further by selling it to the Chicago and Northwestern Rail road Company. If there be any doubt of the cool deliberation with which those eminent capitalists set out to swindle the Government, it must, perforce, be dissipated by consideration of the following fact : When the negotiations were pending for the transfer of the stock of the Sioux City and Pacific Railroad Company to the Chicago and Northwestern, reads the report of the Pacific Railroad Commission, John I. Blair offered a resolution, which appears on the minutes, setting forth that the Chicago and Northwestern must bind itself to protect every obligation of the company except that to the United States Government.